Will Congress just order oil to be cheaper?

The futures market for oil is getting a lot of blame for the rising price of petroleum products, and the add-on increases in prices of other goods and services such as air travel and groceries. But what are futures markets and, if they're so villainous, why do they continue to exist?

First, a definition from the U.S. government's Commodity Futures Trading Commission:

OK ... so it's a bit like gambling, right?

No, not really. It's actually about reducing risk and evening out the financial impact of price changes. The CFTC isn't real clear on why this is so, but let's start with the commission's explanation:

Well that clears things ... Wait! No it doesn't. Leave it to bureaucrats to obscure the utility of even the most beneficial tools. Let's turn instead to an explanation by Robert Murphy, an economist with the Institute for Energy Research:

So futures markets are good things because, while they can serve as a play ground for those evil speculators we've all been warned about, in doing so they actually reduce uncertainty and risk throughout the economy.

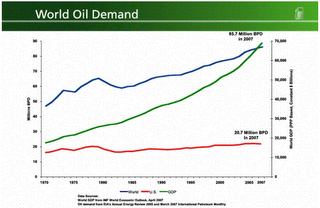

So what's really driving increases gasoline prices? The Institute for Economic Research has a pretty cool interactive feature that explains what's going on. Basically, it's supply and demand -- demand from China and the countries of the developing world has been skyrocketing as their economies grow. U.S. demand for oil has remained pretty static during that time. People in previously poor countries are getting wealthier, and they're demanding more petroleum as they do so.

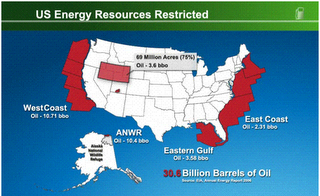

Increased demand relative to supply puts upward pressure on the price of petroleum. That acts as a signal to increase production, but it takes time to do so. Is it taking so long because those nefarious oil companies are getting fat on profits while sitting on their untapped reserves? They wish. Actually, 95% of oil reserves are owned by governments, with only 5% in private hands. That means the oil companies need to cut deals with government officials and get permission to explore for oil and ... well ... there are some pretty promising areas where they're not allowed to explore for oil -- like the East Coast, the West Coast, a big chunk of the Gulf of Mexico and ANWR.

So the reason for rising gas prices, once again, is rising demand, and supply not yet catching up. It's not, repeat, not, evil futures market speculators.

But there's nothing more ignorant -- or worse, indifferent -- about economics than a politician. That's why financial industry lobbyists were on Capitol Hill last week begging Congress not to do anything stupid as part of its ongoing effort to make "speculators" the villains in the current gas-pump morality play.

How did Congress respond?

How unbelievably stupid -- or evil -- do you have to be to end a discussion as to the real causes of a major matter of public concern?

Well, stupid or evil enough to make a career in government, I guess.

Look for lawmakers to put some serious curbs on the futures market, despite warnings from economists that they'll thereby be increasing the level of risk in the economy.

And look for a host of other dumb moves to come down the pike as Congress seeks to demonstrate the superiority of the desires of a room full of ignoramuses over mere economic reality.

First, a definition from the U.S. government's Commodity Futures Trading Commission:

What is a Futures Contract?

A futures contract is an agreement to buy or sell in the future a specific quantity of a commodity at a specific price. Most futures contracts contemplate actual delivery of the commodity can take place to fulfill the contract. However, some futures contracts require cash settlement in lieu of delivery, and most contracts are liquidated before the delivery date. An option on a commodity futures contract gives the buyer of the option the right to convert the option into a futures contract. Futures and options must be executed on the floor of a commodity exchange—with very limited exceptions—and through persons and firms who are registered with the CFTC.

OK ... so it's a bit like gambling, right?

No, not really. It's actually about reducing risk and evening out the financial impact of price changes. The CFTC isn't real clear on why this is so, but let's start with the commission's explanation:

Who Uses Futures and Options Markets?

Most of the participants in the futures and option markets are commercial or institutional users of the commodities they trade. These users, most of whom are called "hedgers," want the value of their assets to increase and want to limit, if possible, any loss in value. Hedgers may use the commodity markets to take a position that will reduce the risk of financial loss in their assets due to a change in price. Other participants are "speculators" who hope to profit from changes in the price of the futures or option contract.

Well that clears things ... Wait! No it doesn't. Leave it to bureaucrats to obscure the utility of even the most beneficial tools. Let's turn instead to an explanation by Robert Murphy, an economist with the Institute for Energy Research:

Although it's true that a particular forward contract can only have positive market value for one party if it has a corresponding negative market value for another, this doesn't at all mean that the "losing" party should regret the transaction. This is because one of the primary uses of forward (and futures) contracts is to hedge away risk. In this type of case, the contract is chosen so that its positive or negative market value (under various scenarios) will offset losses or gains from other sources in those same circumstances.

For example, an airline's profitability is closely tied to the price of crude oil, because their jets use so much fuel. If the price of oil shoots up, operating costs rise and profit margins shrink. (Even if the airline can raise ticket prices, consumers will fly less.) On the other hand, if oil prices fall then the airline benefits.

Yet the price of oil isn't something related to someone's expertise in running an airline. The owners of the airline might prefer to avoid this additional "gamble" by purchasing large quantities of oil futures. If the spot price of oil suddenly rises, the airline is hurt because of the higher operating costs, but this hit is (at least partially) offset by the growing value of its futures contracts.

On the other hand, if the price of oil collapses, then yes the market value of those same futures contracts becomes negative. Yet the airline is fine with this, because the lower fuel prices are good for business and allow them to cope with the loss.

We see that forward and futures contracts can act as a type of insurance policy, where traders can reduce their exposure to fluctuations in critical spot prices by buying or selling the appropriate instrument. To continue the analogy, consider that when assessing the damage in a given car wreck (say), the auto insurer and motorist have diametrically opposed interests. Yet it would be wrong to conclude that the institution of insurance is a zero-sum game.

So futures markets are good things because, while they can serve as a play ground for those evil speculators we've all been warned about, in doing so they actually reduce uncertainty and risk throughout the economy.

So what's really driving increases gasoline prices? The Institute for Economic Research has a pretty cool interactive feature that explains what's going on. Basically, it's supply and demand -- demand from China and the countries of the developing world has been skyrocketing as their economies grow. U.S. demand for oil has remained pretty static during that time. People in previously poor countries are getting wealthier, and they're demanding more petroleum as they do so.

Increased demand relative to supply puts upward pressure on the price of petroleum. That acts as a signal to increase production, but it takes time to do so. Is it taking so long because those nefarious oil companies are getting fat on profits while sitting on their untapped reserves? They wish. Actually, 95% of oil reserves are owned by governments, with only 5% in private hands. That means the oil companies need to cut deals with government officials and get permission to explore for oil and ... well ... there are some pretty promising areas where they're not allowed to explore for oil -- like the East Coast, the West Coast, a big chunk of the Gulf of Mexico and ANWR.

So the reason for rising gas prices, once again, is rising demand, and supply not yet catching up. It's not, repeat, not, evil futures market speculators.

But there's nothing more ignorant -- or worse, indifferent -- about economics than a politician. That's why financial industry lobbyists were on Capitol Hill last week begging Congress not to do anything stupid as part of its ongoing effort to make "speculators" the villains in the current gas-pump morality play.

In a pair of lengthy and sometimes testy closed-door sessions in the Senate last week, executives from Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, two of Wall Street's largest investment banks, made the case that their multibillion-dollar investments in energy contracts have not led to higher oil prices. Rather, they told Democratic staff members of the Energy and Natural Resources Committee that the trades allow international markets to operate efficiently and that the run-up in oil prices results not from speculation but from actual imbalances of supply and demand.

How did Congress respond?

"Spare us your lecture about supply and demand," one of the Democratic aides said, abruptly cutting off one of the executives, according to a staff member in the room.

How unbelievably stupid -- or evil -- do you have to be to end a discussion as to the real causes of a major matter of public concern?

Well, stupid or evil enough to make a career in government, I guess.

Look for lawmakers to put some serious curbs on the futures market, despite warnings from economists that they'll thereby be increasing the level of risk in the economy.

And look for a host of other dumb moves to come down the pike as Congress seeks to demonstrate the superiority of the desires of a room full of ignoramuses over mere economic reality.

Labels: economic liberty, stupid government tricks

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Links to this post:

Create a Link

<< Home