When the political history of the 20th century is written, it's likely to be noted primarily as a period in which the human race willfully returned to barbarism after several centuries of increasing liberty, restrained government and recognition of the value of the individual. Up for grabs, though, is whether it will be treated as an interregnum in the development of free, civilized societies, or the precursor to a 21st century marked by resurgent tyrannical government and the the erosion of liberty. So far, the signs aren't good.

At least in the West, the 19th century was, overall, the liberal century. That's "liberal" in the original sense, as it's still understood in much of the world, a philosophy that values individuals over groups, liberty, limited government, free enterprise and the rule of law. As the Liberal International, which unites liberal political parties and organizations around the world, puts it:

Liberalism champions the freedom, dignity and well-being of individuals. Liberalism acknowledge and respect the right to freedom of conscience and the right of everyone to develop their talents to the full. Liberalism aims to disperse power, to foster diversity and to nurture creativity. The freedom to be creative and innovative can only be sustained by a market economy, but it must be a market that offers people real choices.

In the United States, "liberalism" has generally come to mean something more collectivist and group-oriented. As South Africa's Helen Suzman Foundation, founded but the great anti-apartheid activist, points out:

[I]n the United States of America, however, the way in which "liberals" are defined differs from the South African and European definition. Liberals in the United States include many people who hold "progressive" views in the sense that they are less sympathetic to free enterprise and individualism and more consistently supportive of public welfare. In Europe and South Africa such people are very likely to regard themselves as "social democrats" or socialists, which are less familiar categories in the United States.

The 19th century was a liberal century in the original meaning of the word. That is, it marked an imperfect, incomplete, but very real progression toward a world in which people are valued as individuals and free to guide their own lives and associate with one another with minimal interference from a restrained state. Across Europe and the Americas, monarchies were toppled and replaced with governments that felt compelled to at least pretend they respected individual rights and limits on their power. Despite the liars among them, more people than ever before came to enjoy freedom of the press and of conscience, property ownership, due process and other previously unknown safeguards for their liberty.

Probably the greatest triumph of the century was the widespread abolition of slavery. In country after country, for the first time in history, human beings stopped owning other human beings. The fact that slavery existed at all is still considered an embarrassment, but even questioning the practice is a relatively recent development. For anti-slavery movements to evolve and, ultimately, triumph in most countries, is unprecedented.

The 19th century was a remarkably encouraging century if you value individual liberty.

Then came the 20th century, which combined rapid technological advancement with massive repudiation of liberal values. Suddenly, politicians felt comfortable denigrating the individual and promoting the power of the state even beyond the claims of absolute monarchs of the past.

Then came the 20th century, which combined rapid technological advancement with massive repudiation of liberal values. Suddenly, politicians felt comfortable denigrating the individual and promoting the power of the state even beyond the claims of absolute monarchs of the past.

As Benito Mussolini wrote in 1932, "The foundation of Fascism is the conception of the State, its character, its duty, and its aim. Fascism conceives of the State as an absolute, in comparison with which all individuals or groups are relative, only to be conceived of in their relation to the State."

And Joseph Stalin summed up his view of the world rather succinctly, saying, "Ideas are more powerful than guns. We would not let our enemies have guns, why should we let them have ideas?”

Even the supposedly secure democracies of the 20th centurt flirted with totalitarian ideas. Franklin Delano Roosevelt's National Recovery Administration boasted, "The Fascist Principles are very similar to those we have been evolving here in America."

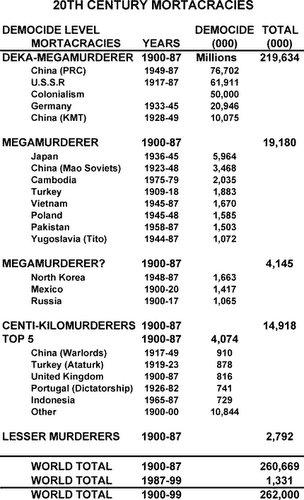

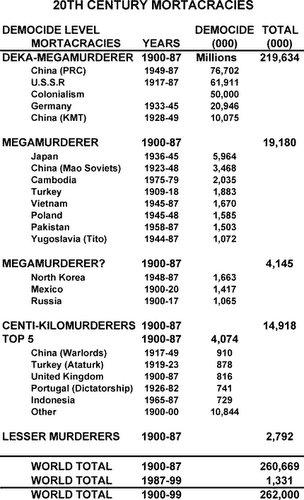

Having repudiated liberty, the totalitarian governments of the 20th century also repudiated life. R.J. Rummel, Professor Emeritus of Political Science, University of Hawaii, estimates that through war, deliberate starvation, genocide, gulags, pogroms and the like, governments slaughtered 262 million people during the course of the last century.

The vast majority of that killing was done by absolute states that had explicitly rejected the previously rising tide of liberty, individualism and limited government that had gone before them.

Basically, big government kills, and it kills in a big way. Even if you don't value the freedom of societies with limited governments, it's impossible to ignore the fact that restrained states bathe in rather less blood than the uncontrolled variety.

Liberalism seemed back in vogue in the latter part of the century. Fascism, Nazism and then Communism were ultimately defeated at enormous cost, while democracy, liberty and free markets were seen as the wave of the future. The all-powerful state of the 20th century looked like a horrible aberration that would be avoided at all costs in the future.

So where are we now?

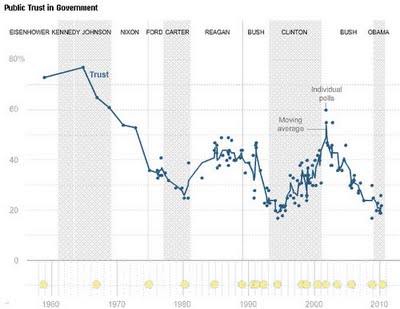

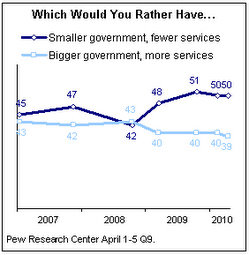

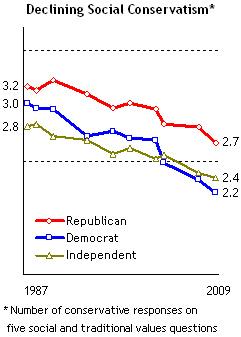

Just nine years into the 21st century, the United States seems to be flirting once again with the idea that the powerful state is a good thing, and that politicians should have more control over our lives than they have been permitted in decades.

We've already had one president -- George W. Bush -- who, without having any recognizable ideology, endorsed a far-reaching and almost absolutist vision of presidential power. In the name of battling terrorism, the Bush administration crafted legal arguments to the effect that the president could unilaterally disregard constitutional protections for free speech, a free press and safeguards against unreasonable search and seizure.

Now, President Barack Obama defends the Bush administration's use of the state secrets doctrine to shield executive actions from investigation and legal challenge, and even goes so far as to defy a court order to produce documents. While quibbling about the details of his predecessors' actions, Obama seems to endorse an expansive view of government power.

And first the Bush, and then Obama administrations have gone farther, returning to fascist economic policies that empower the state at the expense of private choice and individual autonomy.

No, this isn't totalitarianism and nobody is talking about mass murder. But we are seeing a significant and dangerous growth in the power of the state -- a return to collectivist, illiberal principles that threaten liberty. We've tried that path before, with nasty results. Powerful, intrusive government has proven to be a monster that either destroys or is destroyed.

The 20th century was scarred by a brief and bloody mass flirtation with high-tech barbarism. So far in the 21st century, it looks like the old infatuation may still have a hold on politicians' hearts.

Labels: libertarianism

Then came the 20th century, which combined rapid technological advancement with massive repudiation of liberal values. Suddenly, politicians felt comfortable denigrating the individual and promoting the power of the state even beyond the claims of absolute monarchs of the past.

Then came the 20th century, which combined rapid technological advancement with massive repudiation of liberal values. Suddenly, politicians felt comfortable denigrating the individual and promoting the power of the state even beyond the claims of absolute monarchs of the past.