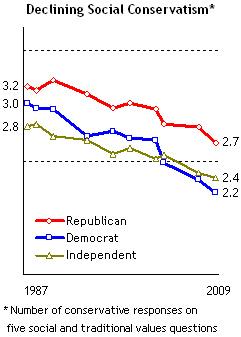

Much fuss has been made in the press about the low regard in which Americans hold Republicans, the stronger position of Democrats, and the ascendancy of Independents who refuse to affiliate with either party. But there's been relatively little discussion of the role Americans' growing social tolerance and concern for civil liberties plays in the GOP's troubles, or the fact that such "liberal" attitudes go hand-in-hand with a continuing distrust of government.

Gallup is getting play with

survey results revealing that about 63% of the dwindling ranks of Republicans are white conservatives. The Democratic Party, by contrast, is more ethnically diverse and is overwhelmingly moderate-to-liberal.

But what do "conservative," "moderate" and "liberal" mean and what implications do such ideological identifiers have for the future?

The answer to those questions might be found in

Trends in Political Values and Core Attitudes: 1987-2009, a publication of the Pew Research Center for People and the Press. The survey doesn't just rely on ideological labels that often conceal more than they reveal, but delves into opinions on social issues, economic matters and the relationship of the individual to the state.

The biggest change in views in recent years, according to Pew, comes in attitudes toward social tolerance and civil liberties. For example, while Americans are still somewhat uncomfortable with outright same-sex marriage (54% oppose, up from 49% last year), 53%

favor civil unions "allowing gay and lesbian couples to enter into legal agreements with each other that would give them many of the same rights as married couples."

We're now at the point where a majority of the population favors marriage for gays and lesbians in all but name.

Overall, the share of Americans saying that "school boards ought to have the right to fire teachers who are known homosexuals" has dropped from 51% in 1987 to 28% today.

It's not just homosexuality, either. Only 19% of Americans say that women should return to their traditional role in society, down from 30% in 1987. And while 71% of respondents still adhere to "old-fashioned values about family and marriage," that's down from 87% in 1987.

In terms of

civil liberties, while 55% of Americans agreed in 2001 that it "would be necessary to sacrifice some civil liberties to curb terrorism," that figure has declined to 27% today.

Interestingly, Republican support for surrendering civil liberties has tracked with national figures, declining from 40% two years ago to 27% today. But eight years of the security state under President George W. Bush have at least temporarily associated the Republican Party with Guantanamo Bay, warrantless wiretaps and state secrets doctrine (though President Obama seems dead-set on making all of that a bipartisan affair).

While 42% of Republicans would allow warrantless searches of the homes of potential terrorism sympathizers, only 34% of Democrats and 30% of Independents agree.

Tellingly, Independents track more closely to Democrats than to Republicans on social values. That's important because "independent" is where the action is, with the ranks of those rejecting both parties growing rapidly in recent years.

And, with important implications for the future, Americans are more socially liberal the younger they are. The "greatest generation," born before 1928 is more socially conservative than the "silent generation" born between 1928 and 1945, which is more socially conservative than Boomers born from '46-'64, followed by Gen-Xers from '65-'76. Today's so-called Gen-Yers are the most socially liberal of all.

Even on an issue where overall attitudes haven't really budged with time -- banning "books that contain dangerous ideas" from libraries -- support for censorship is highest among older Americans and lowest among the young.

But as Americans grow more socially tolerant and supportive of civil liberties, they're not necessarily embracing modern liberalism's love of state intrusion into the economy. That's especially true of those unaffiliated with either major party.

According to Pew:

As a group, independents remain difficult to pin down. They are clearly left-of-center when it comes to religiosity and issues of moral values – independents’ views on homosexuality, gender roles, censorship and the role of religion in politics are clearly closer to those of Democrats than Republicans. They also tend to have more in common with Democrats with respect to foreign policy and military assertiveness. At the same time, their views on broader economic issues have taken a turn to the right in the latest survey. In particular, they are now more conservative on questions relating to the role of government in providing a social safety net and the government’s overall effectiveness and scope. They are also less aligned with Democrats than at any point in the past in their attitudes toward big business.

Specifically

Specifically, 57% of Independents believe "the federal government controls too much of our daily lives." Sixty-one percent of Independents say that "when something is run by the government, it is usually inefficiant and wasteful." And 55% of Independents agree that "government regulation of business usually does more harm than good."

Pew describes this seeming growth in a combination of social liberalism and economic conservatism as "centrism," but that doesn't really explain much. On closer examination, Americans overall -- and Independents in particular -- seem to want a little less government in both their bedrooms and their wallets. They don't want politicians discriminating against gays and lesbians, authorizing intrusive searches or banning books. They also don't want politicians to try to manage the economy or intrude into private businesses.

Americans are increasingly tolerant of each other even as they remain skeptical of the state.

Sentiments are incomplete and inconsistent, but overall national sentiment has apparently drifted in a libertarian-ish direction, favoring more liberty and hostile to government impositions.

Such sentiments might last until the next poll, of course. But they do seem to point to an intriguing -- and encouraging -- future for the country. They also indicate shifts in the population's values and attitudes that the major political parties will have to address if they want to be relevant in the years to come.

Republicans, in particular, have to face up to the fact that their socially authoritarian positions are, increasingly, a minority preference.

Labels: culture clash, libertarianism