Watch out for 'Tea Party terrorists' -- like Paine and Thoreau

For those not in the know, Stack, like many people, had a bone to pick with the I.R.S. and with the federal government. But the manifesto he left behind also accused drug and insurance companies of "murdering tens of thousands of people a year," charged that poor people get to die for the mistakes of the wealthy, and quoted Karl Marx. Anti-government Stack was, but his ideology, such as it was, doesn't appear to have been coherently right-wing or left-wing so much as ticked-off and populist.

Rich does appear to be aware that Stack isn't a very logical stick with which to beat the Tea Party movement that has him and his government-cheerleading chums so knicker-twisted. At least, he concedes "it would be both glib and inaccurate to call him a card-carrying Tea Partier or a 'Tea Party terrorist.' But he did leave behind a manifesto whose frothing anti-government, anti-tax rage overlaps with some of those marching under the Tea Party banner."

Nice how Rich works that gratuitious "Tea Party terrorist" bit in there, eh? But even as he smears his political opponents as guilty by distant and tortured association, he manages to overlook the fact that the anti-government sentiment he so regrets is neither a wholly owned subsidiary of the Tea Party movement and the Right, nor an aberration coughed up every decade or two by by unenlightened neanderthals briefly emerging from the philosophical swamps.

Frank Rich is a well-educated man with an Internet connection paid for by a respected news organization that has a vast historical archive of its own, so it's impossible to believe that the New York Times scribbler is unaware that Thomas Paine wrote in one of the more popular political tracts of the revolutionary period that "government, even in its best state, is but a necessary evil; in its worst state an intolerable one." Nor can we believe he's unaware that James Madison hedged on Paine's sentiments only to the extent that he wrote, "It has been said that all Government is an evil. It would be more proper to say that the necessity of any Government is a misfortune." And certainly he knows about Thomas Jefferson's warning that "[t]he natural progress of things is for liberty to yield, and government to gain ground."

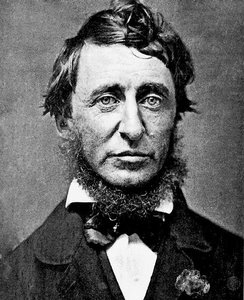

And Rich must surely be aware that he's skipping over a bit of context when he drops the overworked Joe Stack connection to shriek in shock that "[t]he Tea Partiers want to eliminate most government agencies, starting with the Fed and the I.R.S., and end spending on entitlement programs. They are not to be confused with the Party of No holding forth in Washington -- a party that, after all, is now positioning itself as a defender of Medicare spending. What we are talking about here is the Party of No Government at All." Surely, if only in high school, he read Henry David Thoreau's open hostility to the power of the state:

I heartily accept the motto, "That government is best which governs least"; and I should like to see it acted up to more rapidly and systematically. Carried out, it finally amounts to this, which also I believe--"That government is best which governs not at all"...The United States of America was founded on anti-government sentiment. The shapers of its institutions and many of its major thinkers have always clearly viewed the state as something like the equivalent of a portable kerosene heater in a Wisconsin winter -- you might need the damned thing, but be very careful.

True, the fact that the heart and soul of American political history is thoroughly skeptical of government power doesn't mean that Madison and Jefferson were right and that Rich is wrong. Maybe he and his buddies are correct and we should stop worrying and learn to love big, well-armed institutions that claim a monopoly on the use of force and slaughtered 262,000,000 people over the course of the 20th century alone. (It's for the children, don't you know?)

But history shows that anti-government sentiment is in the mainstream of American political life, and Rich and his buddies are the out-liers. No shrieking effort to paint skeptics of state power as kamikaze terrorists -- shoe-horning Joe Stack in with Thomas Paine and Henry David Thoreau -- can change that fact.

Labels: culture clash, media circus